Born Again:

How a middle school nerd found her inner athlete. Twice.

By Julie Tolleson

Out in right field, I cringed. “Please oh please don’t hit it to me.”

My mom had signed my twin sister and me up for softball the summer after we turned 13, and league rules said everyone had to play. So there I was, always in right field, hoping not to embarrass myself, as I suffered through my mandatory two innings. My sister, in contrast, was the starting shortstop.

Born without depth perception and woefully far-sighted, I lacked the hand-eye coordination that separates athletes from geeks in middle school hierarchy. I wasn’t chosen last in PE, but I could see it from where I stood.

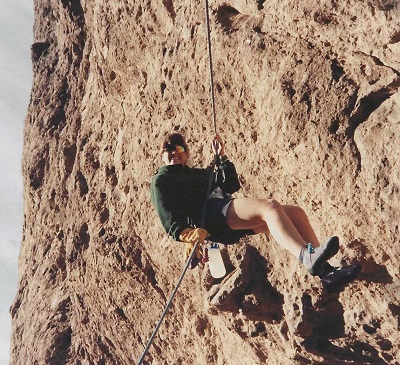

Week-long Grand Canyon Tonto Traverse in 1997

No one ever told me that I could be an athlete. Athletes were people with wiry bodies full of natural speed, or big powerful people with innate strength. And of course athletes were people with hand-eye coordination. Clearly a kid who couldn’t catch a pop up or hit a tennis ball or even run a fast 100-yard (yes it was yards in those days) dash could never be an athlete.

So, I got good grades instead. I went on to college, a top law school, and then into an office in a central Phoenix high rise.

But the Arizona desert called to me like a muse; I just had to explore it. I started to hike. Hiking, you see, was not a sport. It was just a kind of walking, and I did not have to be an athlete to walk. I started to camp, because then I could fall asleep in the arms of the muse.

That first year after law school, my older sister invited me to backpack the Grand Canyon. I was the slowest in the group, and my legs and lungs screamed with every step of the hike back out, but I was hooked. In the three years that followed, I woke up one Christmas morning in the heart of the Superstition Mountains. I hiked the Mogollon Rim, San Francisco Peaks, the Santa Ritas and the Chiricahuas. I lost the map in the Blue Range Primitive area and covered 17 miles in search of water. I continued to explore the Canyon on foot, eventually making over 18 descents, as either backpacking trips or single day crossings.

When my friend Sarah encouraged me to take an eight-week rock climbing course, my middle school anxieties rushed back. But I showed up. I learned knots and ropes and how to trust my feet. When one of the instructors asked if I used to be a gymnast, I looked over my shoulder to see who he was talking to. Climbing was not scary to me, and I am still surprised that so many fear it . Long fly balls are way scarier.

A few years later I moved to Colorado, and I immersed myself in what marketers call the “active Colorado lifestyle.” I continued to climb and added ice axe use and steep snow ascents to my skills. I learned to ski and became an avid cyclist and mediocre runner. I did, you know, things athletes do. And with that came a self-esteem and a transcendent joy in living.

Learning to climb with Arizona Mountain Club Basic School in 1992

My boss at the time prided himself on a certain personal and professional identity. “I am not a litigator. Litigators are paper pushers,” Charlie explained. “I am a trial lawyer.” He spoke the words very deliberately, but it struck me as an example of misplaced priorities. I thought to myself, “Law pays the bills, but who I am is a climber, backpacker, and mountaineer.”

That all came crashing down when I was only 35. Quite literally. A high-speed cycling crash on Squaw Pass destroyed my left foot. When the surgeon said he’d probably need to fuse it, I started to cry. “Are you a climber, doctor?” I asked. He wasn’t.

I would have three more surgeries over the next two years, including a “successful” fusion. “Successful,” but I could not tolerate a climbing shoe. I could not run or hike without pain, and I walked with a slight chronic limp. I threw myself into work. I gained weight and drank too much. I intermittently struggled with depression. I found alternate ways to get into wilderness—including by canoe and horseback—but I never climbed another mountain.

The years ticked by, but the grief and the yearning for what I had lost never fully subsided.

In early 2017 I found a surgeon who was willing to have a candid conversation with me about amputation—an idea about which doctors had been scoffing at me for over a decade. In June of that year, I had my left leg amputated below the knee. I was 53 years old. I had lived 18 years with that crappy foot.

Paradox Sports Ouray Ice Climbing Trip 2016