Chad Jukes Summits Everest For PTSD and Veteran Suicide Awareness

By Sam Sala

The explosion was deafening; the impact of the blast, indescribably violent. While on patrol, running combat security operations in Iraq, Chad Jukes’ vehicle had rolled over an anti-tank mine. In an instant, his entire life, his love of the outdoors, his ability to simply walk or run, would be altered forever. Or would it?

Even before the love of mountain climbing took hold of him in high school, Jukes had always been active in the outdoors. He grew up in Smithfield, Utah, hunting, mountain biking, hiking and backpacking and loved being out in nature in just about any form that took. As he lay in a hospital bed with a broken femur and a shattered, MRSA infected heel, he was desperate to know how his injuries would affect his ability to ever stand atop another peak. He posted about his situation in an online forum and soon received an email from a respected adaptive mountaineer –and co-founder of Paradox Sports– Malcom Daly.

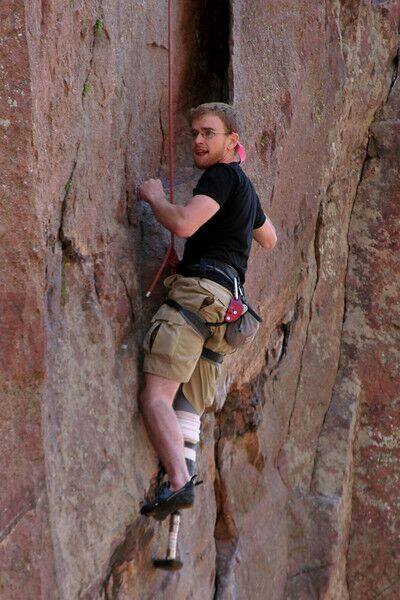

Chad’s first climb as an amputee, with Paradox Sports Bastille Crack, Eldorado Canyon State Park, Colorado

“Malcom,” chuckles the now thirty-two year old retired staff Sergeant, fondly adding, “Some of us in the adaptive community call him ‘The Limb Reaper’. He’s the guy who shows up when you think everything is at its worst, and gives you a whole new perspective and way of thinking about things. He makes you think about what you can do with what you still have; not about what you think you’ll miss out on because of what you don’t have.”

At 25 years old, Jukes made the difficult decision to amputate below his right knee so that he could continue to stay active and pursue his love of the outdoors. He wanted to get back into climbing as soon as he could and decided to attend an adaptive climbing get-together -the newly formed Paradox Sports’ first official event in 2007. Later, Jukes was also introduced to ice climbing via Paradox Sports, at the Ouray Ice Park in Southwest Colorado.

Chad Jukes assisting a participant at our annual Paradox Ouray trip

“My relationship with Paradox [Sports] has had a lot to do with me getting to where I am today,” Jukes pointed out, “A ton of my skills were developed and sharpened at Paradox events. It’s been a great experience to be involved with the organization for so long and to watch my role grow along with them. I started out as a participant, then became an Ambassador, and now I’m also instructing at the Paradox [Ouray Icefest] clinic.”

In May 2016, nine years after first climbing with Paradox Sports post-amputation, Jukes summited Mount Everest. This climb can change your perception on mountaineering. Weather, routes and elevation are all extreme as you make your way to the highest point on Earth.

The team chose the northern route, located in Tibet, for a variety of reasons. First being the avoidance of the Khumbu Ice Fall, a notoriously dangerous stretch of crevasses and precarious, bus-sized blocks of ice that topple over or collapse with little to no warning. The second was avoidance of the massive, and potentially deadly, traffic jams that plague the more popular and highly traveled south side. Another northern route benefit, though not a factor in route choice for Jukes, was the approach.

“It’s really kind of funny,” smiles Jukes, “On one hand, you have the Nepalese (south) side with this remote, 9 day trek just to get to base camp. On the other, you have the Tibetan (north) side that is serviced by these beautiful paved and graded-gravel roads. You literally get off the bus at your tent site.”

“One big thing to keep in mind though is that the Chinese government doesn’t allow air travel, which includes rescue helicopters. If you get into trouble on the south side, you can catch a chopper out and be back down in Kathmandu in a matter of hours. If you get into trouble on the north side… you’re just in trouble,” adds Jukes, “Or if you’re in really bad shape, they can drive you a full day to the border of Nepal where you can get flown out. But then you’re on the wrong side of the mountain and in a whole different country when it’s time to go home.” From the Northern route, the nearest airport is a two-day drive.

Jukes (3rd in line) and team on Everest during an acclimation day

The north route has several technical sections, including navigation of three cliff bands, known as “steps”, all at extreme altitudes. These steps typically have ladders to help climbers scale them, but are known to be sites of potential traffic congestion. The ladders are also known for being oriented differently from year to year, depending on snow levels. This year, below the infamous 30 foot ladder at the second step, a shorter, 10 foot ladder was tied to a large chockstone at its base, leaving the entire ladder slightly overhanging.

“You can imagine it is pretty tough to keep your core tight and make sure you’re fully concentrated on the rungs of an overhanging ladder at 28,000 feet,” Jukes commented, “At that altitude you really have to focus on efficiency and economy of motion. There are times when you would normally make a few quick moves and be done with an obstacle, but up there, you have to measure yourself. If you try to move too quickly, you just collapse in exhaustion. Even the simplest task like lacing your boots in the morning takes a toll on you,” he laughs,”You sit up and lace one boot, lay back down and pant for a while, then sit up and lace the other.”

Chad Jukes standing atop the highest point on Earth, Mt. Everest

But as most know with any climb, getting up is just half the battle…

“Our descent experience was super intense, even life and death at times,” Jukes recalls, “It was very eye-opening and humbling for me. I’ve always been a very cautious climber. I pride myself on being the kind of guy who is willing to turn around, in order to come back and try another day. This definitely made me think about my decision making process and what I could have done differently to prevent it from becoming so harrowing.”

Jukes had been climbing with the team’s camera man, Dave Ohlson, when Olhson started getting sick just below the summit. The pair, along with the Ohlson’s Sherpa, topped out, then quickly made the decision to descend. While still high on the peak, the team was caught in gale-force winds and forced to spend the night in Camp 3, at 8300 meters (~28,140’).

“You’re still well into the death zone at that point, but we didn’t have a choice to move any further because of the conditions.” Jukes affirmed.

The team overnighted at the extremely exposed and isolated Camp 3 then made their way down the next day in slightly better conditions, though even the improved conditions were terrible. They found themselves trudging through uncharacteristically (for Everest) wet and heavy snow, all while being battered by jet stream winds of 65-75mph.

“There were times we were on our hands and knees, crawling to get down. There were a few times where we couldn’t even crawl. We had to sit there in one spot and stay as low as possible. If you tried to get up, you’d just get blown over. And to top it all off, my oxygen line was partially severed at some point, so I ran out of gas way earlier than expected. Essentially I was descending a majority of the upper mountain without supplemental oxygen which really slowed me down,” said Jukes. The slower-than-desired pace during descent, coupled with the harsh conditions and wet snow contributed to frostbite on eight of his fingertips.

Jukes and the rest of his team set out for the 29,035 foot challenge with a purpose: to raise awareness on the issues of PTSD and veteran suicide; both topics very close to his heart as he has lost several friends to suicide in the past year. Sadly, while Jukes was on Mount Everest, Paradox Sports community member and Chad’s good friend, Dan Sidles, took his own life.

“I found out about Dan right when I got back to base camp after my first rotation on the mountain,” Jukes remembers, “I definitely thought about him a lot the rest of the climb. He was such an inspiration when it came to how to talk about [PTSD]. He was always so candid, just totally upfront and honest, with what he was going through and how it was affecting him. It shook me deeply to hear he was gone and took me a quite a while to process.”

In 2010, Jukes and Sidles climbed another Himalayan peak, 20,075 foot Lobuche, along with 9 other veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan and suffered the physical and emotional toll of war. That trip and the training leading up to it sealed their friendship through a mutual love of mountaineering. The climb and their individual stories were featured in the 2012 documentary “High Ground“.

Learning of Sidles death while on the trip reinforced Juke’s sense of purpose to spread awareness about PTSD. “It made it crystal clear to me that I had to be there,” Jukes said, “In a way, it was even fitting that I was on a mountain when I found out. Dan always took such joy from being in the mountains. They really helped him work through things in a healthy way. I’ll miss him, but there will always be a piece of him along with me on every climb.”

Jukes believes PTSD, mental illness and suicide all need to be part of an open discussion in order to reduce the stigma surrounding them. “When you’re involved in a veteran community, unfortunately suicide becomes a regular part of things… Many are striving to change it, but the process can be painfully slow, especially when nobody wants to even bring the topic up,” he said.

Among his concerns around PTSD and veteran suicide are the lack of funding for, and reduced access to, mental health treatment, which results in untreated people “behaving inappropriately and ending up in jail or prison, where they may or may not get the care they need.” He hopes that opening up the discussion on mental health, and finding ways to make relatively small, earlier investments in treatment could result in significant positive changes.

With his successful climb of the northeast ridge, Jukes became the second combat-injured amputee to summit Everest on May 24th – just five days after Boise, Idaho climber, Thomas “Charlie” Linville became the first via the same route. On the south side of the peak, another Paradox Ambassador, Jeff Glasbrenner became the first American-born amputee to summit on May 18th. An adaptive climber from India was also on mountain, but came up short of the summit. Needless to say, 2016 has a big year for adaptive climbing on Mount Everest.

For Jukes, his Himalayan pursuits don’t end with a successful climb of the world’s highest summit. He is currently working on the logistics to return to Nepal, and to get involved in instructing at the Khumbu Climbing Center. Part of the Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation, the Khumbu Climbing Center teaches Sherpa safe and responsible climbing and guiding techniques.

“On Everest, our guides were actually coming to me to discuss weather windows and timing for climbing pushes. It was an honor to have my skills be viewed as an asset by these professionals and I definitely wouldn’t be where I’m at without the support of Paradox. And to get to share those skills would really mean the world,” Jukes said enthusiastically.

Though he is not expecting any long-term issues from the frostbite, his fingertips are still very sensitive and he is not able to rock climb quite yet. For now, Jukes is looking forward to doing some drytooling (climbing dry rock using ice climbing tools) near his home in Ridgway, Colorado, and is making a list of climbs in North America he is hoping to tackle. “The Moose’s Tooth in Alaska is definitely on my short list.” He beams.

For others looking to get started with adaptive climbing, “Just get after it and stay after it,” Jukes suggests, “And of course, get connected with Paradox Sports…anybody can climb. We prove that on regular basis. It may take some time and dedication, but we can make it happen.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.